If you take your game as an MTT player seriously, you’ve undoubtedly heard the term ‘ICM’ by now. You may not be one hundred percent sure what it is, and you may be even less sure how to apply it, but you’ve surely heard people talk about it. There are a lot of misconceptions about the nature of the concept, and in particular about the situations in which it is or isn’t relevant. Traditional logic suggests it’s only relevant at final tables, and that’s true up to a point – but it’s not the whole picture.

First and foremost, I should define what ICM is for those who may be unaware. It stands for Independent Chip Model, a mathematical modelling system whereby each chip in play in a tournament is assigned a mathematical value, according to the total number of chips in play at the start of a tournament, and the total prize pool of the tournament. It allows us to make real-time estimations and retrospective calculations of the actual monetary value of our decisions, by showing us how our decisions affect our equity in the tournament.

The idea of ‘tournament equity’ isn’t something that’s discussed particularly often, and when it is, it’s usually referred to within the context of the question, “how often am I going to win this tournament from this position?” – it’s rarely thought of in terms of how our current stack corresponds to our equity in the tournament’s prize pool. In fact, though, this is one of the most important concepts underpinning a lot of our decisions over the course of a tournament, and one which we utilize unconsciously on a frequent basis.

ICM dictates that every chip we win in a tournament is less valuable than the one that came before it, and our last chip is the most valuable of all. The reason for this is that tournament prize pools are most commonly distributed in a way that sees only around 30% of the total amount go to the first place finisher, so even when we’re the massive chip leader and the ICM value of our stack may technically be greater than first place money, we can’t ever actually make more than first place money, unless we’re able to somehow convince the other players to take a really bad three-handed or four-handed deal.

Conversely, while it’s impossible for us to have 100% equity in the tournament because we can’t win 100% of the prize pool, it’s entirely possible for us to have 0% equity in the tournament and the prize pool – this happens every time we bust a tournament. This means that as much as it might pain the more aggressive players among us to hear it, it is simply more important not to bust the tournament than it is to focus on winning it.

This reality has several effects – it means that once we get to a final table, where most of the tournament’s prize pool is at stake, moving up the pay ladder should be our priority in situations where there is a short stack in play. We will need to make significantly tighter folds than usual, even on a fairly short stack, if there is someone else at the table who is likely to bust the tournament before we do.

It also means that we need to start thinking about the effects of ICM before we even get to the final table, and that’s where most people run into trouble. One of the weaknesses of ICM as a model for analysis is that it doesn’t factor in our future edge against the other players at the table – it assumes all skill is equal. There are other weaknesses to the model, but I won’t go into those right now.

Considering our future edge against the remaining players in the tournament is a dangerous game. It’s tough to put any kind of numbers on it or quantify it in any way. But there are ways we can make it easier. For starters, estimating our edge and knowing exactly where it’s going to come from is much easier when there are fewer players left in the tournament – we know by the time we get to short-handed play what sort of opponents we’re up against and how we plan to exploit them. This makes it at least somewhat possible to plan ahead – change our 3bet frequencies, see more flops, etc. We can develop a strategy.

But how do we develop a strategy for maximizing our edge earlier in the tournament, where there are so many more opponents in play, and it becomes harder to make blanket adjustments? While it’s not possible for us to make precise calculations of the impact on our tournament equity of each of our individual plays throughout a tournament, it is obvious that while we cannot win a tournament in the early or middle stages, we can certainly lose it.

Doubling our stack in level 1 theoretically doubles our equity in the prize pool, but the problem with this is that unless we get our opponent to put all his chips in drawing dead, doubling up usually implies at least some risk of busting. This means we have more to lose than we do to gain when our stack is at risk, and not only that, but even if we don’t bust the tournament, losing a big portion of our stack contributes to neutralizing our future edge over the field.

The only real way we can adjust to this in real-time is to make fewer decisions that lead to big chunks of our stack being at risk early on in tournaments – more flat-calling, more pot-controlling, and less big multi-street bluffs. Not to say we should avoid making big plays entirely, but we need to pick our spots carefully. But given that these adjustments are impossible to calculate precisely in real-time, can we at least develop a system for retrospective analysis of these situations?

What we really need is some kind of metric by which the short-term profitability of these plays can be measured against the potential damage to our stack when they go wrong, and against the effect that would have on our future edge in the tournament, since the effect of losing chips will always be greater than the effect of gaining them. Some way to identify the situations where the risk-reward ratio of a certain play is insufficient.

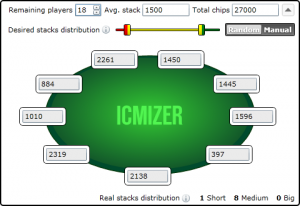

The easiest example to use here would be shoving all-in preflop in blind vs blind situations, since that’s the most truncated form of MTT play. When calculating the profitability of our plays in these spots, using a tool such as ICMIZER, we’re given exact results – we can express, in terms of a number of big blinds, how profitable the play is based on the villain’s calling ranges. Each hand we could conceivably shove with yields a certain level of profit or loss.

Conventional logic dictates that we should shove any hand that’s profitable in these spots, and indeed there are many spots where shoving any two cards can yield a profit. But simply taking every profitable spot is going to lead to very high levels of variance in our game, because those spots that might make us 0.1 big blinds in the long run are never going to add up to a substantial increase in our tournament equity, they’re just going to add up to lots and lots of unnecessary coinflips.

What I would suggest, therefore, is weighing the profitability of a hand versus the amount of big blinds we’re risking, and the approximate edge that those big blinds represent. Identifying a minimum level of profitability that we demand from a play before risking a certain number of big blinds to make it, and altering that minimum level depending on our perceived future edge in the tournament.

When we have a very short stack – say, less than 10 big blinds – it’s hard for us to have any substantial edge, unless the tournament is incredibly soft and players simply don’t have good preflop calling ranges. The best we can hope for is to make profitable preflop shoves, so our profitability threshold is any play that is at all profitable. That’s a simple one. Blind vs blind, this is usually going to manifest itself in a ‘shove any two cards’ kind of spot, against most relatively tight villains.

Once we get above 10 big blinds, however, we have to start thinking about the fact that we may occasionally be able to ‘take a better spot’ – we have a little more space to fold a few more hands before getting blinded down, so taking any marginally profitable spot might not be necessary. We do have some kind of edge with 10-15 big blinds, so we might want to demand a 0.5 big blind profit on a preflop shove in order to compensate for this. Obviously in a tougher tournament we can reduce this number, and in a really soft tournament we might want to increase it to 0.75 or so.

Above 15 big blinds, we get to the point where we actually have way more options than just shoving preflop, so if we’re going to get it all-in, we should make sure we’re pretty confident in the profitability of the play. We still have plenty of room to exercise a future edge on 15-20 big blinds, so if we’re going to get that amount of chips in preflop – particularly if we’re the effective stack and our tournament life is at risk instead of the villain’s – then we should demand around a 1 big blind profitability threshold from the play.

After that 20 big blind inflection point, we need to be very confident in the plays we make. We need to know that we’re risking that big chunk of chips for a reason, because our future edge with 20 big blind effective stacks could be significant. This means we should demand a profit margin of 1.5 big blinds or higher. The number of hands with which this profit margin is achievable will be relatively narrow, and this is a great example of the ‘tightening up’ necessary as our stack increases.

The interesting thing about these profitability thresholds is that they correspond very closely to the kinds of ranges that most people intuitively believe are appropriate in many spots. Based on the analyses I’ve conducted during my recent coaching sessions, a common trend is that when a spot comes up where a good player is telling me what kind of range they would shove for 15 big blinds in a certain spot, the range they assign is usually very close to the range of hands which yield a profit of 1 big blind or greater.

This indicates that even though we may not be associating this particular idea with the concept of ICM, many players are in fact making these decisions already – they’re just not retrospectively analysing them and assigning profitability thresholds. They’re turning down spots because they’re ‘too marginal’, without quite being able to say exactly what makes them marginal – the answer to ‘what makes them marginal’ is simply that they don’t make us that much profit in the long run, and we have to risk a number of chips in order to make the play in the first place.

So while you may be aware of the impact of ICM on final table play, and you may already be performing ICM-based analyses of your final table situations, be aware also that the concept of ICM extends throughout every tournament you play. It might not be quite so easy to quantify in the earlier stages when your equity in the prize pool is harder to define, but the concept is still there. The reason why we make tight folds at final tables is because there’s more to gain from folding than calling or shoving – even more so when we have a strong edge on the field.

Thus, in the early and middle stages, we should be folding a lot too, when our stack or a big portion of it is on the line in a marginal spot – it’s simply correct, and it’s more correct the bigger our future edge. There are plenty of players out there who neutralize their own edge by taking so many marginal spots that their game becomes a series of coinflips, and unless you’re playing an astronomically high volume of MTTs, that’s a dangerous practice.

It’s important to note that this doesn’t necessitate a tighter overall approach – indeed, you can still 3bet bluff to your heart’s content and steal the blinds all day, because those plays are only risking small portions of your stack. But the more of those plays you make, the more often people are going to play back at you and force you to risk bigger portions of your stack, so a balance is appropriate.

Everyone wants to be aggressive and take advantage of their skill edge against the field. But each portion of your stack represents a certain amount of future edge, and the more you put that edge at risk for a small reward, the more it’s negated. Next time you’re retrospectively analysing your play, think about your profitability thresholds, and ask yourself whether ‘profitable’ is really profitable enough.

markconkle

Thanks for the article. A lot of things to think about.

While it’s certainly true that ICM can be important before the final table, I think you need to be more cautious about making decisions based on future profitability edges. First, let’s think about some numbers. You argue if we have 20BB we should be passing on +1.4BB decisions that put our stack at risk. That’s 7% of our stack. Given that generally when we are risking our stack by calling, we will only lose the tournament about 50% of the time, this is assuming a 14% edge on the field with a 20BB stack. While a 14% edge is very reasonable at the start of the tournament, I would argue that in most online tournaments it’s difficult to have that big of an edge with 20BBs. Even if we SHOULD have a 14% edge, do we STILL have it after deciding to pass up a bunch of +ev spots?

If we are risking our stack by shoving, we will frequently be in a spot where our chance of busting is more like 20%. To pass on a +1.5BB shove spot demands that we have a 35% on the field with 20BB. This seems patently absurd in all but the softest of tournaments.

Each time we pass on a profitable spot due to our future edge, we are actually decreasing how much of an edge we have, by making what is a priori the WRONG decision.

Another fault I have with this idea is that it doesn’t take into account the value of our time/monitor space/attention. While in live tournaments it’s often true that once we bust, we are going home, when playing online, busting often means starting another tournament. If the new tournament is of equal quality to the one we busted, we aren’t really missing out on any skill edge by busting early in the tournament. Certainly when we have 5 times a starting stack, our skill edge will be greater in terms of $ because we are effectively playing a higher buy-in, so we should consider these factors when deeper in a tourney and in particularly soft/valuable tournaments, but it’s not something to mindlessly apply to every tourney on our screen.

TLDR: When risking your stack, consider what the chance is you actually bust. Marginal shoves are better than marginal calls. If the tourney is nothing special, your tournament life is also nothing special.

folding_aces_pre_yo

I need to start looking looking into ICM so much more , this article has helped for sure , but i still struggle with it.

jedimindpicks

Excellent article. Very interesting points brought up here.